The policies of Sri Lanka’s new government: a historic opportunity lost

Éric Toussaint reviews the situation in Sri Lanka since 2022. From the popular revolts to the new centre-Left government elected in late 2024 and the negotiations with the creditors, this overview provides a better understanding of a country whose social, economic and political situation has much to teach us yet remains widely unknown. Éric Toussaint compares events in Sri Lanka with what took place in Greece in 2015 and in Argentina between 2019 and 2023, with the attendant risk of a hard-Right government coming to power in the future.

Sommaire

- Can you give us a quick summary of the crisis in Sri Lanka in 2022?

- So the popular uprising was the result of economic factors?

- What happened after President Gotabaya Rajapaksa fled the country?

- What was the outcome of the 2024 elections?

- Does the change mean that the commitments to creditors made by the country under earlier (…)

- Doesn’t what is happening with the new NPP government recall what happened in Greece in 2015 (…)

- Can you summarize the debt obligations that the previous Sri Lankan governments have contracted (…)

- What’s the situation with Sri Lanka’s bilateral debt?

- What measures can be taken to get out of this vicious circle?

- And what about the private debt of the working classes?

- One last question: Are there people in Sri Lankan society who take a critical point of view (…)

Can you give us a quick summary of the crisis in Sri Lanka in 2022?

It began with a popular revolt in March-April 2022 which continued through July of that year. The revolt was the result of several shocks undergone by the country which caused a serious economic crisis, with:

- The effects of a terrorist act in 2019, which resulted in a drop in tourism

- The international coronavirus pandemic, which put completely halted tourism in the country starting in 2020

- The effects of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which caused a rise in the cost of the fuels, grain and fertilizers imported by Sri Lanka and paid for in US dollars.

| For more information: Sri Lanka’s Crisis is Endgame for Rajapaksas |

The combined effects of these factors resulted in a general suspension of repayment of public debt in April 2022. The situation had suddenly grown worse because of the effects of the Ukraine war on the price of imports in late February 2022 and the decision by the central banks of the USA, Europe and the UK to suddenly raise their interest rates in February-March 2022. That made the situation of Sri Lanka all the more untenable, since the country did not have enough revenue to pay for its imports of fuels, food and fertilizers whilst at the same time servicing its debt, which explains the necessity of the payment default. Finding money in spite of all this became totally impossible due to the hikes in interest rates by the US Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank and the Bank of England. Investment funds like BlackRock, who had bought up large quantities of Sri Lankan debt securities over the previous years, were unwilling to lend any more to the country unless it offered extremely high yields – on the order of 15% or more.

So the popular uprising was the result of economic factors?

Yes, they were the triggers. But during the demonstrations the people’s anger was turned against the president, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, whose family had held the presidency since 2005 (except for the period between 2015 and 2019). The government had become extremely unpopular due to the regime’s corruption and the accumulation of wealth by the president’s clan. On 13 July 2022, the demonstrators forced President Rajapaksa to flee to the Maldives, then to Singapore, invading the presidential palace and even bathing in his private swimming pool.

What happened after President Gotabaya Rajapaksa fled the country?

The problem that arose was that there was no popular political force with enough of a base within the population to replace the Rajapaksa clan, and the population had not really taken on the goal of actually taking power. As a result, the same clan remained in place, with Raniil Wickremesinghe, who was Rajapaksa’s Prime Minister, taking over as President of Sri Lanka. And in the end the president who had resigned and fled into exile returned a few months later without any reaction from the population.

| For more information: ‘The Canary in the Coal Mine’: Sri Lanka’s Crisis is a Chronicle Foretold |

Another problem was the fact that all the mainstream commentators, but also the intellectuals from the Marxist and Communist side, along with most Keynesian economists, felt that there was no alternative to loans from the International Monetary Fund.

Starting in April 2022, the country’s authorities began negotiations with the IMF and the holders of sovereign debt securities in order to secure credit with the IMF, on the one hand, and a restructuring of the “commercial” debt with the bondholders. The goal was also to arrive at a restructuring or else agreements for postponement of repayment with the bilateral creditors, which was achieved in June 2024.

Negotiations with the International Monetary Fund extended through to March 2023, at which date an agreement was reached on a loan of USD 3 billion and an initial disbursement of USD 333 million was made. A draft agreement was also made with holders of sovereign bonds in September 2024, two days before the presidential election. The agreement was later confirmed by the new authorities.

What was the outcome of the 2024 elections?

What was the outcome of the 2024 elections?

In September 2024, the presidential election was easily won by a candidate of the Left who promised radical change.

In September 2024, the presidential election was easily won by Anura Kumara Dissanayake, a candidate from outside the political establishment – the elites and the parties that had dominated up until then and controlled the government. He is “young”, a leftist, with Marxist origins whilst at the same time having 30 years of legislative experience, and promises radical changes. As soon as he took power he called early legislative elections, which were held in November 2024. The elections were a success for the political alliance backing him, called NPP (National People’s Power), which took 63% of the vote and more than two thirds of the seats in the Parliament (159 seats out of a total 225).

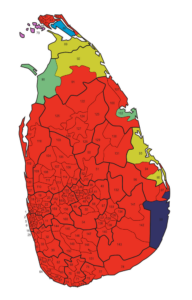

The areas in red correspond to constituencies where the NPP alliance won a majority in the November 2024 legislative elections.

Source : AntanO, CC, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2024_Sri_Lankan_parliamentary_election.svg

President Anura Kumara Dissanayake and his parliamentary group had the means to adopt any law they saw fit to adopt, and even to change the constitution, which requires a two-thirds vote by the Parliament.

Does the change mean that the commitments to creditors made by the country under earlier governments will be called into question?

Despite its promises of sweeping change, the new government of Sri Lanka has not broken the agreement entered into with the IMF and the private creditors. Yet it could have done so on the basis of international law

No, the NPP Alliance, the President and his government say that they will ensure continuity of the State’s obligations. That means that they will maintain the agreements entered into by the preceding government with the IMF and with the bondholders and the bilateral creditors.

This creates an enormous problem, because a historic opportunity, a unique one for the country, is being lost or squandered. Because under international law, a change of government or of regime opens the possibility for the new government to renounce earlier debt commitments if the debt being claimed against the country is odious in nature.

In this case the NPP could definitely say that there has been a change of regime, since the people clearly demanded a change of regime through its massive vote for the NPP and its candidates, most of whom are newcomers. The situation is indeed a regime change, because the people refused to re-elect members of Parliament who in some cases had held their seats for decades. The population elected new faces out of a desire for fundamental change. Therefore from the point of view of the majority of the population, there has been a change of regime. The NPP alliance called for fundamental change, but according to the government that fundamental change did not apply to commitments to creditors. Yet if those commitments are not called into question, there has been no authentic change.

The Sri Lankan government could point out the odious nature of the external public debt and repudiate it.

And further, without moving immediately to repudiation, under the current circumstances the government could suspend repayment, with the justification that the country has undergone a fundamental change of circumstances and a series of external shocks since 2020 (the pandemic, the effects of the war in Ukraine, drastic price increases and interest-rate hikes by the central banks of the countries of the North). Suspension of payment would be perfectly justified under international law, and creditors would not be able to levy arrears on unpaid interest.

Therefore a historic opportunity is being lost due to the authorities’ insistence that they will ensure continuity of debt obligations.

Doesn’t what is happening with the new NPP government recall what happened in Greece in 2015 and in Argentina between 2019 and 2023?

The disappointments that will be created by the NPP’s current orientation also create the risk that the hard Right will return to power in a few years

Yes, in spite of the differences, the situation recalls what happened in Argentina with the general elections in late 2019 and in Greece in 2015.

In Argentina’s case, in October 2019, the Peronist alliance Frente de Todos (“Everyone’s Front”) obtained a majority in both houses and brought Peronist Alberto Fernández to the presidency after conducting a campaign against the neoliberal president Mauricio Macri, who was supported by the IMF and Donald Trump, then president of the United States. During the election campaign, the alliance that backed Fernández had repudiated the agreement Macri had made with the IMF in 2018 as being totally illegitimate, and had promised fundamental changes. Keep in mind that the IMF had granted credit in an amount of USD 45 billion in 2018 – the largest in its entire history. But very quickly, Fernández and his government began negotiations with the IMF and finally re-borrowed USD 45 billion in March 2022 in order to continue repayments. The government also instituted a policy of austerity at the demand of the IMF and Argentina’s capitalist class. That resulted in a huge disillusionment among the Peronist electorate, and in late 2023, an outsider from the extreme Right, Javier Milei, carried the election and launched an offensive against the people on a scale that Argentina had not seen since the dictatorship of the 1970s.

| To find out more about Argentina between 2018 and 2022: Eric Toussaint: “Eric Toussaint: “The IMF agreement with Argentina is perversely sophisticated”” interview by Martín Mosquera for the magazine Jacobinlat, published 7 June 2022, https://www.cadtm.org/Eric-Toussaint-The-IMF-agreement-with-Argentina-is-perversely-sophisticated Also see: A country is entitled to refuse to repay a debt |

In Greece’s case, the Left coalition Syriza handily won the election of 25 January 2015, after a campaign that promised a fundamental break with the IMF, the European Central Bank and the European Commission, together called the “Troika.” But on 22 February 2015, less than a month after their election victory, Syriza and the Finance and Economy Minister, Yanis Varoufakis, asked the Troika to prolong the Memorandum of Understanding instead of ending it as they had promised during the election campaign. Greece paid nearly EUR 6 billion to the IMF in five months. Then, in spite of a popular referendum on 5 July 2015 that massively rejected the Troika’s conditions, Syriza and Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras signed a new agreement with the IMF, the ECB and the European Commission and continued austerity policies and privatizations for four years. Those policies resulted in the hard Right taking a firm grip on Greece’s government in the person of Kyriakos Mitsotakis, who brought members of the extreme Right into his team.

| To find out more about the Greek experience, read: “Greece 2015 – From hope to capitulation, Lessons for the future” by Eric Toussaint, published 25 January 2025 |

It’s important to keep these two precedents in mind, because in Sri Lanka, the disenchantment that will result from the NPP’s current orientation also creates the risk that the hard Right will return to power in a few years in a context where the extreme Right is on the offensive worldwide.

Can you summarize the debt obligations that the previous Sri Lankan governments have contracted with private creditors?

The agreement with private creditors is very bad for the country if we compare it to a series of agreements obtained by other countries in the past

Concerning the agreement with the private creditors, it applies to Sri Lankan sovereign-debt bonds, which were under suspension of payment since March or April 2022. Remember that the private creditors were granted a draft agreement by the preceding government two days before the presidential election of September 2024. That was in violation of the country’s election laws. In fact it was a manœuvre designed to impose on the people and on the new president an agreement that went against the interests of the nation and the popular will as expressed in the voting booth. Subsequently, the new government ratified this harmful agreement, whereas it was not required to do so.

Returning to what happened after the suspension of repayment of 2022, the price of Sri Lankan government bonds on the secondary debt market had dropped to 20% of their initial value. Thus a whole series of bondholders had re-sold the securities to other holders. The negotiations led to an agreement under which Sri Lanka committed to trading the securities in suspension of payment for new securities that represent a little over 85% of the value of the old securities. The country committed to paying an interest rate in the neighbourhood of 6.5%, increasing to more than 9% and possibly as much as 9.75% starting in 2032. If economic growth starts again, the conditions will be even more favourable for the private creditors. This is an extremely harmful agreement for the country, as we can see from the chart below, which shows a series of debt reductions put in place in various countries since 2000.

Graph 1 : Sovereign debt haircuts

Source: Dhanusha Gihan Pathirana, “Sri Lanka’s International Sovereign Bond Restructuring,” Policy Perspectives November 2024, p. 11 https://www.cadtm.org/Sri-Lanka-s-ISB-Restructuring

Other countries such as Ecuador, Russia, Argentina, Serbia and Ivory Coast have agreed to debt restructurings comprising much larger “haircuts” (partial cancellations of the debt). Ecuador was granted a haircut of nearly 70% in 2009. Argentina, in 2005 at the time of the first restructuring of its debt after 3 1/2 years of suspension of payment, obtained a cancellation of 76.8% of its debt. So as we can see, this agreement is a very bad one for Sri Lanka – barely a 15% reduction. Keep in mind that given the interest rates to be paid out, in the final analysis the actual amount to be repaid will be at least 2 billion more than it would have been had the earlier conditions – prior to the September 2024 agreement – been maintained.

And the major investment funds like BlackRock are the ones who benefit most. It must also be kept in mind that creditors who purchased debt bond from a country like Sri Lanka were full aware that they were taking risks. They had already been granted a high interest rate with a risk premium; it would have been absolutely logical for them to accept a much bigger a haircut.

For the investment funds and banks who bought the bonds on the secondary debt market when the price was lowest, the rate of profit is absolutely colossal. If you bought a bond at 25% of its initial value on the secondary market at the height of the crisis – in 2022 – and are then offered to exchange it for a bond worth 85% of the initial value, you can make an enormous profit. When the agreement was signed on 19 September 2024, Sri Lankan bonds were being sold on the secondary market at a reduction of nearly 50%. Which means that on that day, whoever had purchased bonds at 50% of their value made a killing, since they could immediately trade them for bonds worth 85% of the initial value.

Sri Lankan economist Dhanusha Gihan made a comparison between the agreement signed in 2024 by Ghana and the one Sri Lanka entered into that same year. You should know that the agreement signed by Ghana was itself widely criticized by many organizations who are active regarding the issue of debt because it was too generous to the private creditors. In fact, the agreement signed by the former Sri Lankan authorities with the private creditors is a good deal worse.

Demonstrations in Colombo (Sri Lanka) in spring 2022.

Photo : Supun D Hewage, CC, Pexels, https://www.pexels.com/photo/people-protesting-outside-a-building-12860493/

Here is what Dhanusha Gihan says about it: “The Agreement-in-Principle (AIP) entertaining the interests of the creditors at the expense of the general public is further revealed by comparing the Sri Lankan case with Ghana’s debt restructuring. The government of Ghana rejected a disastrous proposal like that of Sri Lanka made by its international creditors. It reached an agreement with 90% of bondholders, meaningfully reducing both principal and interest payments. Ghana secured a 37% haircut on outstanding sovereign debt, while the maximum interest rate applicable for new bonds was capped at 6% as opposed to 9.75% for Sri Lanka. As a result, its nominal debt relief amounts to US$ 4.4 billion (The Africa Report, 2024) as opposed to increase in nominal payments of Sri Lanka by up to US$ 2.3 billion.” [1]

The Agreement-in-Principle signed by the country’s former authorities two days before the election of September 2024 – an election in which that former regime was totally disavowed – clearly went against the interests of the country and its population. The new authorities should have declared it null and void in order to be in a position to renegotiate it on a new basis, or else simply repudiate the amount being claimed by the private creditors, who were in cahoots with the preceding corrupt regimes and were earning fat profits up until 2022. In confirming the agreement of 22 September 2024, the new authorities were working against the interests of the population and in the interest of the private creditors.

Graph 2 : Composition of Sri Lanka’s external public debt (September 2024)

What’s the situation with Sri Lanka’s bilateral debt?

Sri Lanka struck an agreement with its bilateral creditors in June 2024 concerning debt worth USD 10 billion (out of a total of 11 billion). That agreement comprises no reduction in the volume of the debt claimed by the bilateral creditors. What changes are the interest rates, which have been reduced to 2%, and the schedule of payments, which have been postponed. In addition, the start of repayment of the capital has been moved up to five years. The main bilateral creditors are China (USD 5 billion), Japan (USD 2.5 billion), India (almost USD 1.5 billion), and Germany (USD 200 million).

And the agreement with the International Monetary Fund?

The IMF is pressuring the government to privatize, to reduce social spending and to increase indirect taxes whose burden is born by the working classes

The agreement with the IMF concerns credit amounting to close to USD 3 billion, as I explained earlier. The current debt to the IMF is approximately USD 1 billion, and it will increase in the coming years as disbursements are made by the IMF. This loan from the IMF is being granted with draconian conditions. The IMF demands that the government reach a primary surplus of 2.3% on the public budget before the end of 2025. The government will have to reduce public expenditures drastically to reach that goal. And given that there had been very few expenditures on productive investments, productive public investment will be reduced more or less to zero. The obligation to find a primary budget surplus will ineluctably be met at the expense of social expenditures. Pressure from the IMF will also be ramped up to force increases in taxes paid by the working classes, since the IMF never asks for increases in taxes on major multinational corporations, or taxes on wealth, or on stock dividends…

| To find out more: Bailing Out the Creditors |

To give you an idea of the situation, debt service this year amounts to more than the State’s entire revenues. And since the State’s revenues are less than the debt service to be paid, paying that debt requires an enormous financial effort that consists in borrowing funds – from the IMF, for example – just to pay interest on previous loans. Needless to say this is a very bad situation for the public finances and the start of a vicious circle of dependence on creditors.

The IMF is also pressuring the government to undertake further privatizations of public companies. Some privatizations have already been made, but the IMF, just as it does in other countries, wants to privatize a large number of additional companies, including in the electricity sector, which is a vital one for the population. Privatizing the electricity sector will directly cause price increases, resulting in enormous difficulties for the population and a reduction in families’ purchasing power.

For more information on the government’s policy as regards the IMF’s requirements, see the Box below. If you prefer not to go into the detailed figures and technical aspects, you can skip the box.

| Box. According to the economist Amali Wedagedara, the sooner Sri Lanka exits the agreement with the IMF, the better.

Sri Lankan economist Amali Wedagedara, a member of the CADTM, who analysed the 2025 budget, which takes the IMF’s demands into account, wrote on 22 January 2025: “The Budget 2025 illustrates the drudgery of making ends meet inside a debtors’ prison. The Appropriation Bill for Budget 2025 reveals the fiscal squeeze and constraints imposed by the IMF program and the struggle to set the economy on a developmental trajectory. (…) Instead of empowering the Government to upgrade the hardware and strengthen the structural power of the economy – boost industries, restore developmental infrastructure, and elevate skills and technology, the IMF program limits planning and action to the bare minimum and vulnerable sectors like tourism. The Appropriation Bill and, subsequently, the Budget 2025 are early warning signs of the harms of the IMF program. The earliest exit would mean the best for Sri Lanka. In accordance with the IMF guidelines, the NPP Government is striving to meet a 2.3% primary account balance in 2025. Increasing the Government’s revenue to 15.1% of GDP from 11% in 2024 is one initiative to meet the primary Budget surplus. However, the IMF debt sustainability guidelines ensure that the enhancements in Government revenue will not be used for developmental activities and economic recovery but to meet debt servicing obligations. Accordingly, debt sustainability targets that the IMF imposes on the Government’s fiscal planning only ensure the sustainability of the creditors. The Government has capped spending at Rs. 4,290 billion. Interest rate payments will amount to around Rs. 3,000 billion. According to the Governor of the Central Bank, Sri Lanka has to service between $ 4 to 5 billion of debt in 2025. As a result, debt servicing as a share of Government revenue exceeds expenses on social security, public services and investments in the productive economy. A study comparing the debt service obligations of 145 countries in 2024 ranked Sri Lanka 2nd in terms of countries with the highest debt service to revenue ratios in the world (“Resolving the Worst Ever Global Debt Crisis: Time for a Nordic Initiative?” 2024). Total debt service as a share of Government revenue in Sri Lanka is 202%.” [2] |

What measures can be taken to get out of this vicious circle?

Foreign multinationals pay a tax of 15% on their profits, whereas national companies, and in particular medium-sized ones, pay 30%

Taxes need to be increased on companies who can contribute more. You need to know that foreign multinationals pay a tax of 15% on their profits, whereas national companies, and in particular medium-sized ones, pay a tax of 30%.

Indirect taxes on consumption, such as the VAT, account for the majority of the revenues taken in by the State. Over the period January-August 2024, the VAT accounted for a third of the government’s revenues, compared to 25% for January-August 2023. [3]

Direct taxes on the wealthiest taxpayers and those most able to contribute must be increased radically. Indirect taxes on the working classes also need to be reduced in order to increase their purchasing power. It is a known fact that for the working classes, a reduction in taxes and an increase in purchasing power have as a direct result an increase in consumer spending. Thus the measure would have a multiplying effect on the economy. It would mean revenue for third parties, which could create jobs, etc.

But the policy pursued by the IMF is the exact opposite: increase indirect taxes – which will decrease the revenue of the working classes –, freeze wages in the public sector, and force job cuts among public-service employees to reduce public expenditures.

Sri Lanka’s agreement with the IMF must be ended.

The debt claimed by the IMF meets two of the criteria that define an odious debt.

First criterion: the debt with the IMF has been contracted in order to conduct policies that are contrary to the interests of the population.

The conditionalities imposed by the IMF have a nefarious effect on the living conditions of the population and further weaken the country’s economy.

Second criterion: the creditors were fully aware of this, and were complicit in these policies.

There is no doubt that the IMF is aware that the policies it recommends or dictates are contrary to the interests of the population, since the conditionalities the IMF itself imposes make living conditions more difficult for a majority of the population.

If the government organizes an audit with participation by the citizens to analyze the debts claimed by the IMF and request a balance sheet of the policies recommended and dictated by the IMF for the past 20 years, it could have in hand a tool for justifying a repudiation, or at least suspension of repayments, of the debts claimed by the IMF. Credits granted by the multilateral institutions should also be audited: the World Bank (to which Sri Lanka owed USD 4.5 billion dollars in the 3rd quarter of 2024), the Asian Development Bank (to which the country owed USD 6.5 billion dollars in the 3rd quarter of 2024), etc.

The policy imposed by the IMF and accepted by the new government – extending privatizations and promoting public-private partnerships – should be abandoned.

Concerning the debts claimed by private creditors, which amount to approximately USD 15 billion, the audit could also demonstrate their illegitimate and possibly odious nature and justify repudiation, or at the very least suspension of payment pending a re-negotiation that would be favourable to the interests of the population. The private creditors have been complicit with the corrupt regime that led the country between 2005 and 2024 and have made abusive profits.

Concerning the bilateral debts, which amount to USD 11 billion, they should also be audited, regardless of whether they are claimed by China, Japan, India, Germany or other countries. A large share, if not all, of the bilateral debts can be considered illegitimate since they have not been used to finance projects that are actually useful for the country’s population; rather, they serve the interests of the countries who have supported major infrastructure projects that are useful to them – for example, China’s building a deep-water port at Hambantota.

For all categories of debts, the Sri Lankan authorities must put an end to secret diplomacy: all contracts, all documents relating to negotiations on debt must be made public. Because in fact what is published by the Ministry of Finance, the IMF, the World Bank and the bilateral and private creditors makes up only a very small part of the total documentation. What is published is only the tip of the iceberg and is meant to legitimize the debt. If what is kept secret were to be revealed to the public, people would be more aware of the harm done by policies of indebtedness.

Measures also need to be taken regarding internal public debt, which accounts for 60% of all public debt and amounts to approximately USD 60 billion. This is due to the fact that the local capitalist class and the elite who traditionally frequent power have invested in internal debt. They do it because it brings in a high level of revenue, given that the interest rate on internal debt securities is as high as 16%, whereas the Sri Lankan banks, who purchase part of the securities, pay only around 8% to obtain financing. [4] Consequently, they make fat profits at the expense of the public purse, like the rich rentiers who can invest part of their savings in return for a very high yield without lifting a finger, whereas the country sorely needs productive investments. The first measure to be taken would be to halve the interest rate the State pays to holders of internal debt securities.

And what about the private debt of the working classes?

In 2022, more than 200 women committed suicide due to harassment by micro-credit lenders

Concerning this issue, measures must absolutely be taken against abusive and usurious micro-credit, which affects a large proportion of Sri Lanka’s working-class women. The new government should deploy a policy to protect people from indebtedness under abusive conditions. In 2017 and 2018, an initial series of protests by cooperatives and women’s groups in the provinces of northern and eastern Sri Lanka made it clear that many micro-credit companies were charging usurious interest rates of from 40% up to 220%. These demonstrations also showed that the companies used financial and physical violence against indebted women.

Demonstration by women victims of microcredit in Colombo in 2019 (photo Eric Toussaint)

A UN report shows that approximately 2.4 million women contracted micro-credits in 2018. [5] That is the equivalent of one third of Sri Lanka’s 7.8 million adult women (according to the Department of Census and Statistics). In 2022, more than 200 women committed suicide due to harassment by micro-credit lenders. [6]

Therefore the government needs to fight against the micro-credit abuses practiced in Sri Lanka by large local and international banks. A maximum interest rate should be set for this type of loan. It should implement a public credit system for the working classes whilst also supporting women’s cooperatives who organize their own ethical micro-credit programs. The government could, via legal channels, order a general cancellation of debts below a certain amount and below a certain threshold of revenue per indebted person or household.

| About micro-credit abuses in Sri Lanka, see: – “Damning testimonies of microcredit abuse” by Eric Toussaint and Nathan Legrand, published 18 April 2018, – “IMF: Inhuman at the micro and macro levels” by Eric Toussaint, published 27 February 2020 |

One last question: Are there people in Sri Lankan society who take a critical point of view toward the IMF and toward their government’s policy regarding debt?

I’ve just participated in a program of activities in Sri Lanka organized by a number of structures: CADTM international, the Bandaranaike Centre for International Studies, the Economics Department of the Faculty of Arts, Peradeniya University; I was also interviewed at length by a major private television channel. During these activities, I met with many economists, professors, students, journalists, activists, and leaders of social movements who take a critical attitude toward the government, in particular as regards the IMF and debt in general. As part of the CADTM’s programme, we also met with Harshana Suriyapperuma, the Deputy Minister of Finance of the new government, who told us that the government would ensure the continuity of obligations contracted by the previous government. When we pointed out to him that the NPP’s election platform mentioned the need for a debt audit, the Deputy Minister told us that it would come later – each thing in its proper time, so to speak. Lastly, we met with political organizations of the Left who are opposed to the agreement with the IMF. Over the course of this busy programme of activities, I was able to see that a significant number of people adopt a leftist critique of the government and of maintaining the agreements with the IMF and the other creditors. But it is undeniable that they are a minority within the population and that there is a race against time to raise awareness of the dangers inherent in the government’s current approach.

The author would like to thank Amali Wadagedara for information about microcredit and Maxime Perriot for rereading.

Translated by Snake Arbusto.

14 February

is a historian and political scientist who completed his Ph.D. at the universities of Paris VIII and Liège, is the spokesperson of the CADTM International, and sits on the Scientific Council of ATTAC France.

He is the author of Greece 2015: there was an alternative. London: Resistance Books / IIRE / CADTM, 2020 , Debt System (Haymarket books, Chicago, 2019), Bankocracy (2015); The Life and Crimes of an Exemplary Man (2014); Glance in the Rear View Mirror. Neoliberal Ideology From its Origins to the Present, Haymarket books, Chicago, 2012, etc.

See his bibliography: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%89ric_Toussaint

He co-authored World debt figures 2015 with Pierre Gottiniaux, Daniel Munevar and Antonio Sanabria (2015); and with Damien Millet Debt, the IMF, and the World Bank: Sixty Questions, Sixty Answers, Monthly Review Books, New York, 2010. He was the scientific coordinator of the Greek Truth Commission on Public Debt from April 2015 to November 2015.